|

| Haydee Canovas. Photo – Lorena Miller. |

By Rachel White

Entire contents are copyright © 2013 Rachel White.

All rights reserved.

Haydee Canovas is a family nurse practitioner

and theater lover. She has been doing theater around Louisville for two years now

with her company El Deliro. Recently Haydee has teamed up with Carlos Manuel

and others to form a new company for the Spanish Speaking Community, Teatro

Tercera Llamada.

Rachel White: Where are you from originally?

Haydee Canovas: I grew up in South Florida. There’s a large

Cuban community there, and at home we just spoke Spanish and lived our culture.

RW: Did you go to theater a lot as a family?

HC:

I would go to theater with my godmother and my piano teacher. We’d go to

theater or we’d go to Flamenco shows.

RW: Tell

me about your new company, Teatro Tercero llamada. How did you get started?

HC: Four of us, Francisco Juarez, Mable Rodrigues, Carlos Manuel

and myself got together and decided to found a Spanish Language theater

company.

RW:

What is the significance of the name?

HC:

Francisco suggested Teatro Tercera Llamada because he always liked to

say right before the show starts “Tercera llamada” or ‘third call, show’s

starting.’”

RW: Had you worked together before?

HC:

Our first theater company was El Deliro. I was one of the co-founders

and the producer.

RW:

Did El Deliro lead to Teatro Tercera Llamada.

HC:

They wanted to go a different way than I did. I just want to be with

people that want to do theater.

RW:

What is your mission with this new company? How are you different from

other companies?

HC:

We want to do Spanish language plays, but we also want to incorporate

the community because we are a community theater.

RW: In what ways have you reached out to the community?

HC:

We’re working with La Cacita Center in May or June of next year. They

have a group called Sembradoras, the planters, part of the Professoras de

Salude, the mothers of health. The women of La Cacita Center are committed to

giving back to the community by teaching people about health. We’re going to

get the same group and we’re going to teach them how to do theater.

RW: Do you do any shows in English?

HC:

Not yet. There are lots of people doing theater in English, right?

RW: Right. What plays are you doing now?

HC:

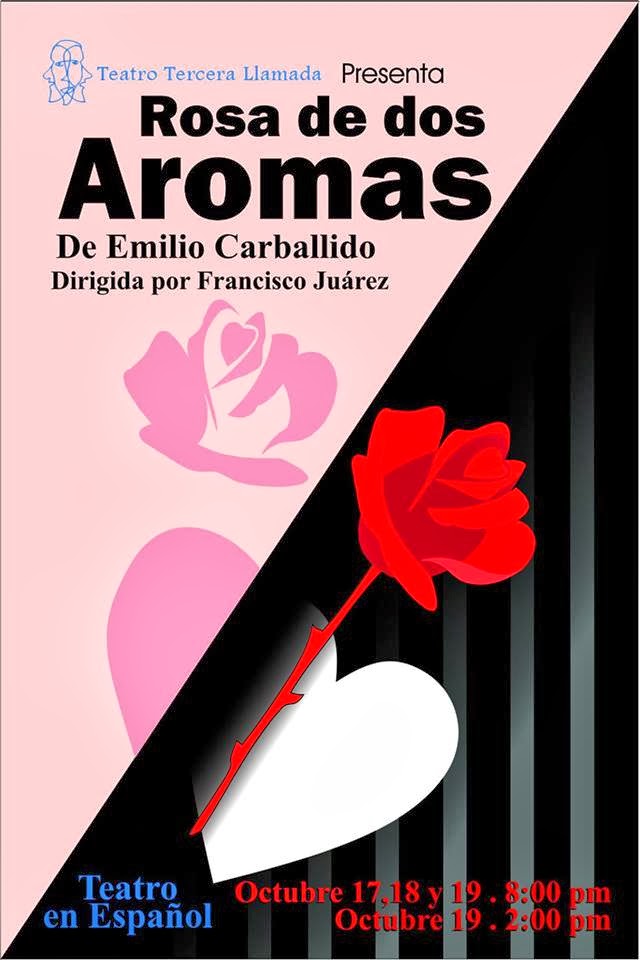

We plan to do two plays a year, and one of those is Rosa De Dos Aromas (A Rose of Two Scents) by Emilio Carballido. It

has been the most produced play in Mexico. And then we have Almacenados (Warehouse) by David Desola.

He’s a playwright from Barcelona who is really picking up steam. Almacenados is playing now in Mexico

City and also ran in Paraguay. We’re the first company in the United States to

do it.

RW:

Can you tell us a bit about the plays?

HC:

They are both comedies. Rosa De

Dos Aroma is about two women: one of them is a sophisticated university

graduate; the other one is a hair stylist. They meet in the lobby of a prison. Amalcenados is about two Cubans: one is

a playwright; and the other is an actor. One is old and one is young, and they

work in a warehouse. That’s what is planned for the first half of next year.

We’re still up in the air about next fall. But we have plenty of time.

RW: Do you often perform authors who are well known?

HC: Whatever the director wants to do. The rule is if you want

to direct one, then you pick your own play and we’ll support you.

RW: Have you gotten a good audience response so far?

HC:

Absolutely. Thursdays are not filled up, but Fridays are usually full

houses.

RW:

Has the response surprised you?

HC:

I met a girl at World Fest, from Honduras, who recognized me from the

show and she wasn’t the only one. I wasn’t expecting that. I just want to do theater

because I love the storytelling and I love to exercise my mind. Carlos put my

picture up on our webpage page. I said, “Take that down.” He said, “Get used to

the fame.”

Rosa De Dos Aromas por

Emilio Carbadillo runs October 17-19

Almacenados por

David Desola runs October 24-25

Teatro Tercera Llamada

at The Baron’s Theater

131 West Main Street

Louisville, KY 40202

;++Isaac+Woofter+(Heart);+Lute+Breuer+(Hind).+Photos+by+Frankie+Steele.+.jpg)